Threads and concurrency on big softwares

While I was working on Forgejo, I’ve started to write a feature for the addition of an option to migrate from Forgejo instances, because before users had to use Gitea option (which Forgejo is forked from) to migrate repositories from both Forgejo and Gitea instances like codeberg or gitea.com. But while studying how to do it I saw that the migration of repositories were not made directly, but rather transformed into a task (normal go struct) that holds some data related with the migration itself and then saved it into a queue. But what happens after this item is added in this queue?

Concurrency

One of the greatest powers of Go is its support for concurrency that can create user-land lightweight threads and at the same time be idiomatic with built-in support for goroutines and channels. When we work with small examples to learn concurrency we may not see too much utility on it and we may never use it in small softwares but in this case of migration we can learn a lot with a real world example. Let’s begin explaining what is a migration, why it need support for concurrency and how it’s done.

What is a migration

When we want to clone a repository on another git service, e.g., from github to gitlab we can start a migration process which will clone the codebase as well commits and another things like issues. These migrations generally rely on some API caller that will make specific requests for the origin based on the options the user choosed to migrate, if you don’t want issues of course it wouldn’t call external API to retrieve it.

Migration and concurrency

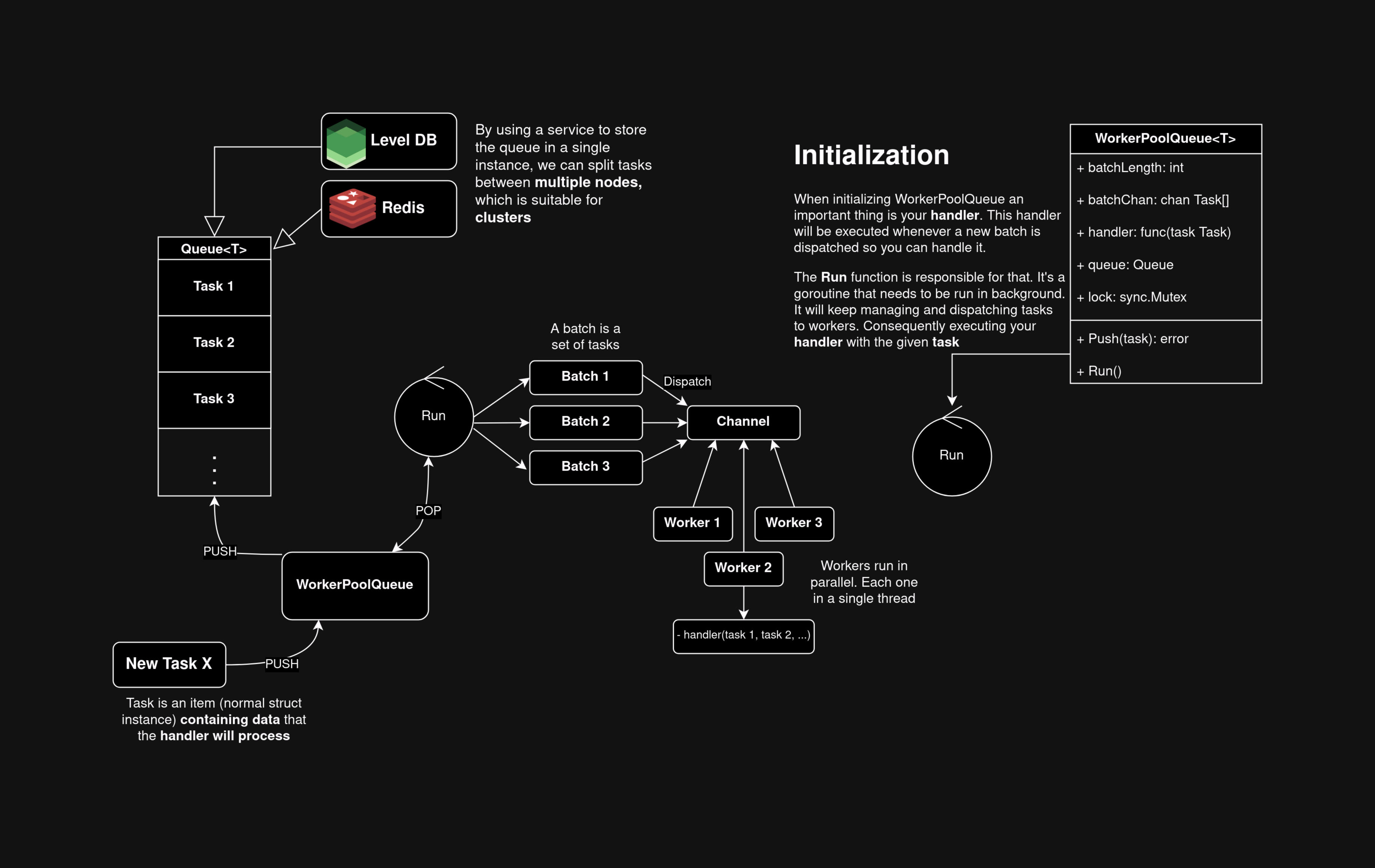

Imagine you’re migrating 10 repositories at the same time. I suppose you don’t want to stay blocked until it finishes. This situation requires multiple threads running under the same application. But also we don’t want all migrations to run on the same separate goroutine/thread. We need a new execution for each one so we can ensure parallelism. But what if we keep creating goroutines even if max of CPU physical cores was reached and some threads already finished their work? Actually by doing this we’re creating stack and scheduler overhead and not an efficient use of CPU. Also, what if the system was distributed? I mean, forget about migrations and Forgejo by now, just think that we may have a software that we may want to scale, but goroutines are not designed to be aware of distinct machines. How do you split work in this system? We need something clever

Thread pool

The concept of a thread pool isn’t that new and not even focused on distributed system or to fix goroutine/migration problems. It’s only a design pattern to achieve cases where an agnostic (by agnostic I mean both distributed and monolitic system) powerfull parallelism must be achieved. It’s aim is to hold enough number of threads on background (by enough I mean something close to the number of physical CPUs) and some Queue where we will can distributed some work across these threads (often referred as workers). First we will create a normal queue that will be responsible for storing items that represent a unit of work, these items will contain the data needed to work on, e.g., a migration, like URL, repository name…, let’s call this item a task. Now, we’ll create a handler (normal function with an task parameter) capable of work with these tasks, that is, giving any task (like migrate with gitlab or github) it will be capable of operate and finish it. Now create N numbers of goroutines, where N is the number of phyisical cores, let them idle (in Go you can just let it listening to a channel). Now create a Manager who will start to dequeue this queue to retrieve tasks and start to distribute across these multiple workers. Congrats, if everything was done correctly we ensured maximum parallelism and thus we will can migrate our repositories very quickly, and also as I said before this Queue is agnostic, we can use reddis to implement this Queue and make multiple machines get tasks on a microservices architecture.