Low-level network and internet

I want to start this by taking inspiration from the OSI model, trying to follow a bottom-up approach where we first start with the problems. Then solve it using intuition and how people solved it in real life. Then, we see where this solution isn’t useful and dive into more abstract things like the layer 3 and beyond, always maintaining an intuitive logical reasoning.

The OSI model is divided by layers, but doesn’t keep yourself too tied to this nomenclature since it’s just a way to tell how abstract we are in network schema. For example, layer 1 is the physical network layer, where data is transformed into electrons or waves if we’re using wifi. We’re assuming these mediums of data flux are already configurated, this means you have a cable where electrons can flux freely and be correctly interpreted as digital data by another point on this cable. So let’s start by layer 2

Layer 2 (data link): Local network, the beginning

Well, lets suppose we have PC 1 and PC 2 and they have no OS. We want to share data between them. Well, let’s plug a cable between them and call this cable ethernet, now we create a function on both devices called send_data(data) and read_data() that’ll just send data to this cable and read. Now we have a connection and can share some bits. But wait, this means we would have to unplug this cable and plug into a PC 3 if we want another connection. Oh, that’s not so good!

Remember. In this layer, we don’t have IP, routing rules, OS, NAT… we are in a very primordial and simple environment. Like the middle of 60s

We need something called network! I want to send data to whatever PC or device I want without keeping plugin and unplugging cables. Ok, we need some device that every device will be plugged and send data, and once this happens, it will forward request to whatever device I want. Let’s call this device a router. But how will this device know which device forwards a network packet?

We need some identifier for each PC, lets call this identifier a MAC Address (every network card comes with a unique 48-bit MAC address by default). Now we modify a little our send_data function to send_data(mac, data). Remember, this router is just another device with this send_data function. But it keeps track of a table with each MAC address bind to one ethernet cable.

Now, jumping on the real world, this process has a lot of details didn’t cover. In fact, every device will have an OS, to continue the explanation we suppose we’re using linux, even routers are usually just a lightweight linux. Now, this send_data we were talking about is implemented in most operating systems as interfaces.

Interfaces: why so subestimated and how linux implements it.

Network interface is a connection between a device and a network, you can write data in it, and it will appear into another point, just like our send_data function did when sending data to a router. One device can have more than one interface, and you can list them using ip addr showcommand.

Every device on the network including our router will have interfaces to communicate between each other. An interface is bind with a MAC address (and usually an IP, but I’ll talk about it later). Your PC probably will have at least 2 interfaces, a loopback (which redirects packets to your own machine), and a local network interface which binds your PC with the router and the local network, it’s generally called enp3s0 in linux systems if you’re using ethernet. There can also be virtualized interfaces that I’ll talk more in a future post about docker network.

Now, interfaces is a very important concept because your data travels through it. In a local network, you don’t need more than that. There are some protocols like ARP that serve for device discovery on the network, making your PC keep track of a table showing which devices exist locally and their MAC Address, so you can send data directly to it.

But now we want to talk with the outside world and get out from LAN. How can we do that? Well, MAC addresses alone can’t help us because they don’t have routing information. We need to create a new identifier for machines outside with some routing policy.

Layer 3 (IP): Going outside

What if we take inspiration from cellphone numbers where we have two layers: International direct dialing (IDD) that serves to represent a country and Direct Distance Dialing (DDD) that represents a state? This is almost like how IP works, it’s a protocol not just an identifier and in fact, it doesn’t care about countries, it works in a very decentralized way. Let’s explore more them.

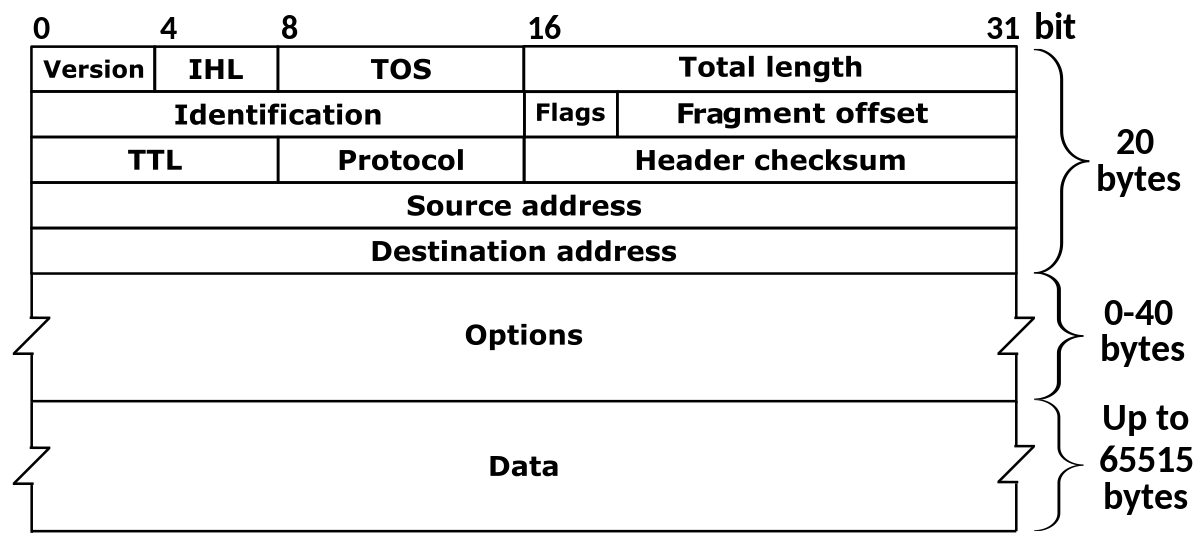

We generally think about IP as just the address: 192.168.100.2, for example, but IP, or Internet Protocol defines a set of rules of how data going outside should flow. For example, it defines every device should have a unique IP, that every frame (data flowing on layer 2, inside LAN) will now be wrapped into a packet, with information like a source, that is, who is sending the request, destination, the address of the device we want to deliver this data. Here’s an image showing how an IP packet looks like:

In this layer we’ll have the definition of default gateway, the device where data is sent to access the internet, generally represented by your modem/router. Now, I said internet works in a decentralized way because the flow after packet goes outside LAN is a mess, it goes through lot’s of gateway, asking him if he knows where IP 10.x… is. Then, this packet is redirected to some place closer to this address he is looking for. If you install wireshark and bound it to your routers main interface, you’ll see packets reaching that aren’t from or to you. But since most of the connections are encrypted, this is no problem.

And this protocol is so important that even local devices will be attached with an IP, because probably you want your PC to talk with another PC in another country, this is why interfaces often are bound with some IP (generally the interface that connects your PC with the network will have your unique local main IP). You may ask who gives this address for my device? It’s the DHCP server defined on your router that gives non-existent IP to every machine on your local network.

But we exceeded the limit of IPv4 years ago. Every device can’t have a unique IP, this is one of the reasons LAN still exists. We use a strategy called NAT(network address translator) to communicate the outside world. The router gives to us local IP using its pre-defined subnet mask. A subnet mask is a rule that says which part of address is common for devices and which needs to be unique locally. It’s generally something like 255.255.255.0, this it’s saying the last part should be unique for the local devices. This subnet mask is also often used to see if a packet belongs to the LAN. It checks the packet destination IP through bitwise using subnet mask and if it matches its local, so it extracts the .0 part to redirect to the local device

NAT and its implications

The only real and unique IP that exists is your ISP IP. It’s the only thing web servers see when receive a packet reaching from you. But how they redirect it correctly? For example, when you join www.google.com how it responds with the appropriate html to your PC? When your packet reaches at ISP, it opens a unique port with its public IP just for you, and it keeps track of a table with your corresponding local routers IP. This is a bit hard to grasp, but your routers ip is also local, this means your neighbor, if using the same ISP can have the same IP from you.

The real difficult comes because there’s two levels of NAT, one happening inside your home to deliver data to your devices and a CGNAT happening at ISP level delivering data to the right local devices to it. But both your router and your ISP open a single point of connection just for you. When web servers respond to your request they just see your ISP providers and a port, but this port is mapped for you.

This is why we should start to use IPv6, maybe we can stop those complex workaround having enough IP for every device in the world.

Layer 4: TCP and UDP

I’ll talk very briefly about TCP/UDP since most people already know about it. These protocols are related to the delivery of packages in a proper and reliable way. What happens is, IP is good to deliver whatever data we want, but alone we cannot ensure data was sent in the correct order without losing any data. TCP is good to ensure reliable data deliver, it defines some headers with complex checksums and splits the data into tiny parts, so if we end with a wrong packet, it’s trivial to ask for the resend of the package. UDP, on the other hand, is good when we don’t need that amount of reliability, and it’s okay to have some data lost over the way. The advantage is that it has less bloat, thus less size and use less bandwidth.

Conclusions

Networks is a vast subject, but for a software engineer knows the basic of it can be crucial, especially if he must deal with distributed systems and multiple servers across the world. Even locally, you’ll have services that depend on ports and protocols, like databases. Or if you’re docker and k8s fan like me, you’ll have to understand interfaces, the different types of network like bridge, host, macvlan… or even a backend API developer that often needs to work with http protocols.

I hope I helped you to understand more about fundamental aspects of the internet and how the network was built. Have a good day!